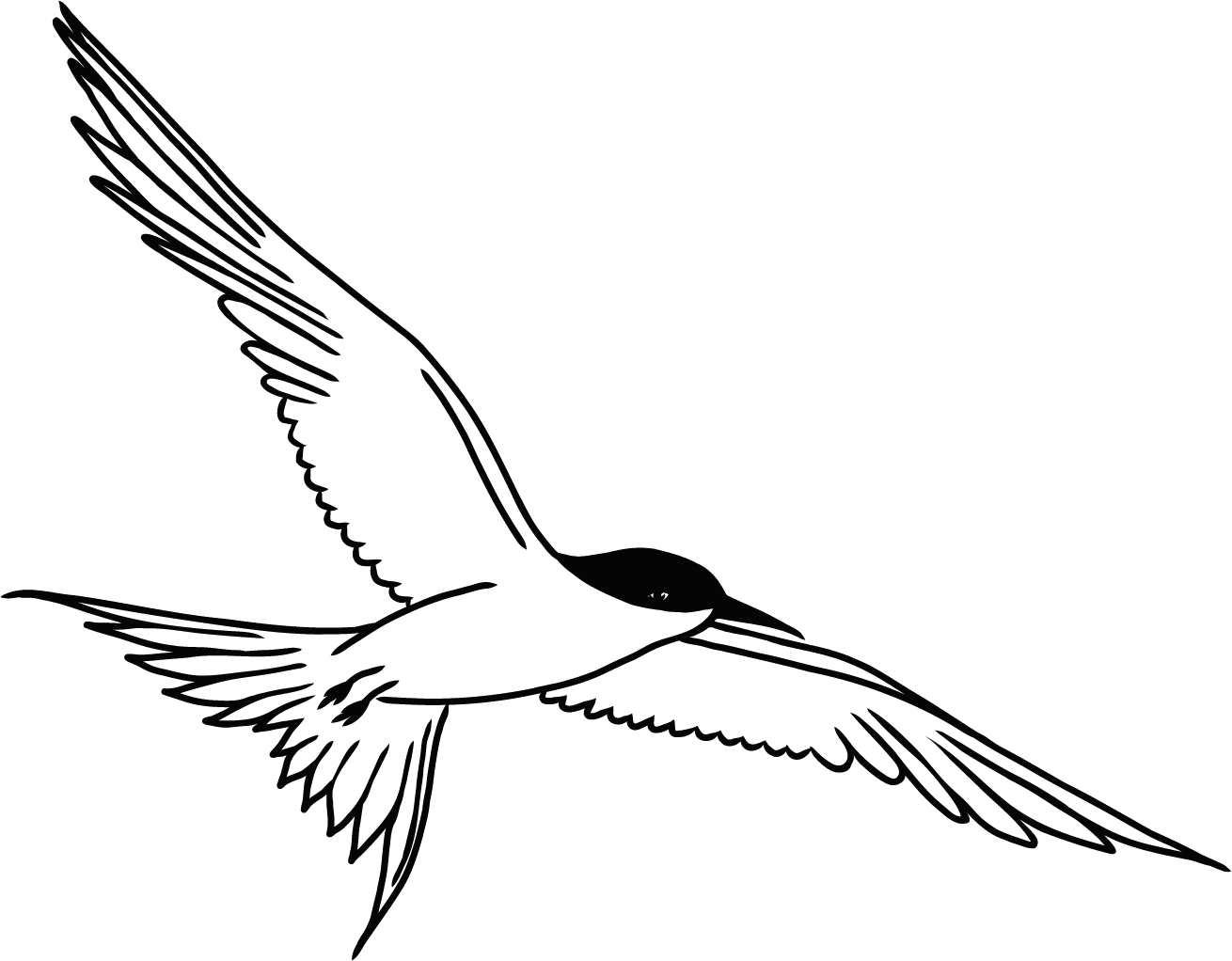

Tara / White-fronted tern

Tara: Cruisers of the coastline

White-fronted terns are only found in New Zealand.

Habitat: Coastline and coastal cliffs, estuaries, river shingle and sandbanks across Aotearoa.

Breeding season: October - January

Diet: Small fish like smelt, pilchards, anchovies, young fish and occasionally shrimp or other small crustaceans.

What’s their superpower?

Tara (aka white-fronted terns) are incredible hunters with wildly impressive agility in the air. Hunting in flocks that can reach the thousands, they’ll hover, swoop and perform mid-air acrobatics above the waves before plunge-diving up to 10m to snatch their next fishy meal.

Why do we need them?

As part of the food chain, tara are crucial for keeping fish numbers in check. Their droppings act as a natural fertilizer for the ocean, nourishing marine plants and feeding coastal vegetation. Plus, they’re a signal of marine health: when tara are doing well, it usually means the sea is too.

Did you know?

Around a week after hatching, baby tara leave their nests to join other chicks in groups known as crèches. Several parents take turns feeding and watching over them until they take their first flight at around 5 weeks old. The reason? When food is scarce or predators lurk, chicks have a better chance of surviving.

Fascinating facts

Fishy courtship: Male tara woo females by offering fish mid-flight. They dive, catch a fish, then present it during aerial displays until a female trails alongside and accepts. Once she takes the fish, the pair bond for the season.

Coast-to-coast commuters: In autumn, many young tara and some adults cross the ditch in search of food and warmer weather before returning home for spring nesting.

Steel squatters: Though rare, tara occasionally nest on flat man-made structures like old steel or concrete surfaces in the harbour if they can’t find a safe natural spot on the coastline.

Nestless natives: They’re one of few birds that don’t build traditional nests. Instead, they make shallow scrapes in open sandy beaches or shingle banks, nesting side-by-side with other tara.

Surprisingly long-lived: These birds can live 18+ years, with the oldest recorded tara reaching 26 years, an impressive innings for a seabird.

Beach hoppers: One season they might settle in to nest on a sandy beach, the next on a rocky island or harbour wall. Their breeding spots are always changing, thanks to shifting tides, predators and human activity which puts them off returning to the same spot.

Conservation corner

Sadly, tara are classified as At Risk – Declining by DOC. Their numbers have taken a big hit over the last 4 decades as nesting sites have been washed away in storms. Unleashed dogs and introduced predators like stoats, ferrets, cats and rats also put eggs and chicks at risk.

How you can help

Keep well clear of breeding sites, especially during breeding season.

Leash dogs near coasts in nesting season.

Support predator control and dune restoration projects in your area.

Pick up rubbish at the beach. Plastic and fishing line can be deadly to tara.

Spread the word. Let others know these birds need space to raise their young.

Help us to help the Tara / White-fronted tern

The tara's nest takes no time to build, as it is usually just a depression on the ground without any nesting materials at all, though they will sometimes add a few small stones at the bottom of the nest. They are especially vulnerable to stoats, ferrets, cats, and rats, and disturbance by people and their dogs. They are currently listed as 'Declining'.

With over 75% of our indigenous species at risk of extinction*, the Pest Free Waitākere Ranges Alliance is raising funds to help defend the many special species of the Waitākere Ranges.

Thank you for your support of the tara!

Whatipu / Tara / White-fronted tern Supporter Gear

Support the conservation efforts of Pest Free Waitākere Ranges Alliance!

By shopping with us, you're contributing to the protection and preservation of our ngahere, and supporting our vision of a restored and thriving Waitākere Ranges.

Choose from a range of clothing and accessories printed with our exclusive design by local artist Celeste Strewe featuring Whatipu's special species – the Tara / White-fronted tern.

Find out more

Image credits: Fern by Toby Hall on Unsplash • Tara in flight by BHINZ • Tara on beach by Emily Roberts